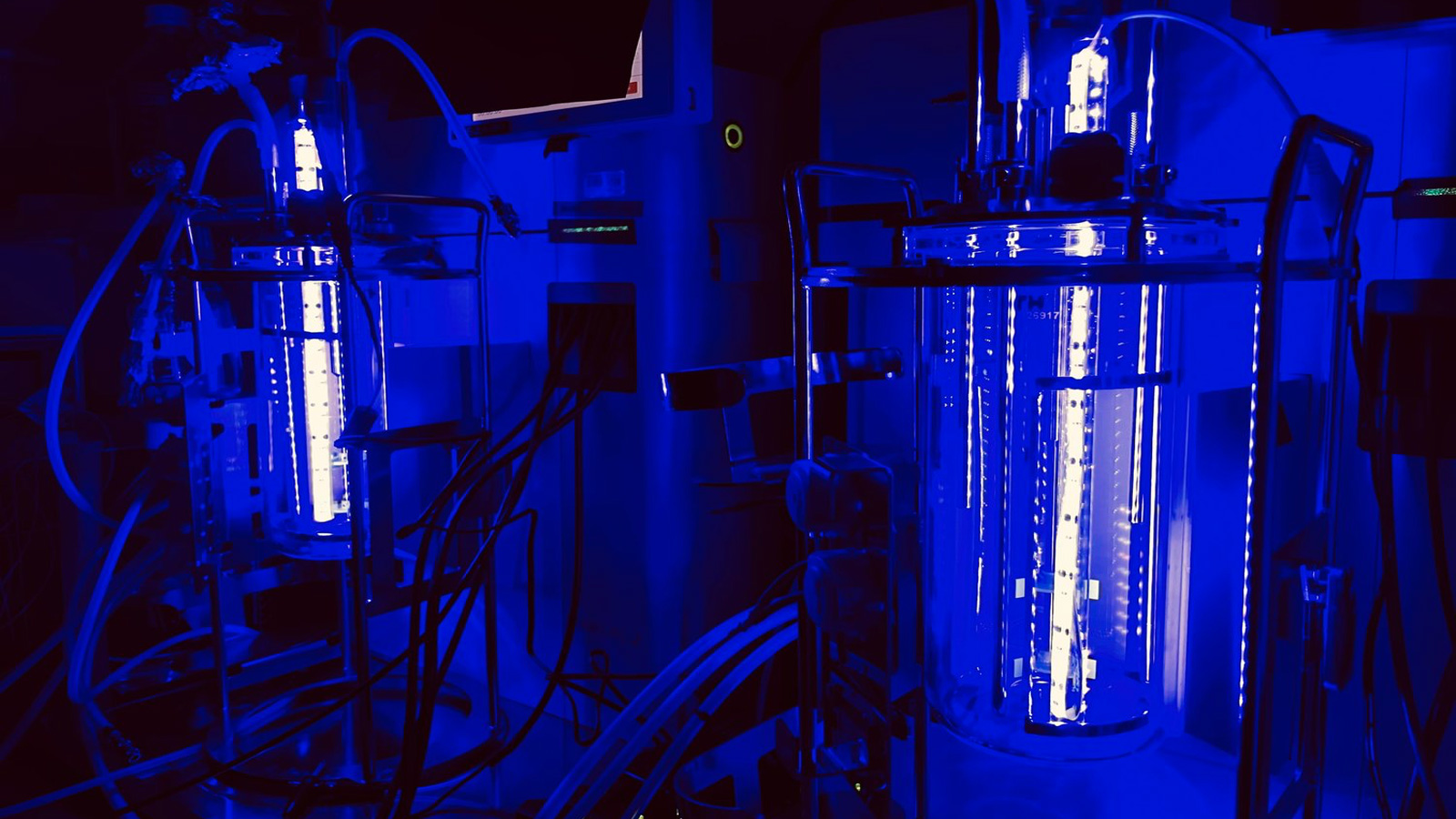

Synplexity makes lots of custom-sequence DNA, cheaper, longer, and more numerous than anybody else.

Enabling up to 1500x the scalability of current technologies

SynPlexity prints massively parallel amounts of DNA sequences – longer and cheaper than anything else. SynPlexity’s tech will unlock new levels of experimentation and training data for synthetic biology and generative protein AI.

Craig Stolarczyk, CEO & Co-Founder

"Unlocking biology requires harnessing the full power of high-throughput screening and machine learning. We eliminate the bottlenecks, delivering synthetic genes at a scale, 100,000 to 1,000,000 genes, at a price that makes ambitious experiments feasible."

Synplexity has raised $520,000 from SOSV's IndieBio and others.